Sarah Feng

Redshifting & Blueshifting in the Worlds of Poetry

4.

Does that obscure our vision of reality?

Using the Doppler effect, we can measure the speed of two stars orbiting each other in a binary star system. By looking at the distortion of our perception, we can pinpoint information about the actuality of spacetime.

When stars in binary star systems orbit one another, each alternatively is blueshifted and redshifted. By using spectrometers to take spectroscopy images, which show an object’s range of electromagnetic wavelength radiation, we can determine the velocity of those stars, and here is how:

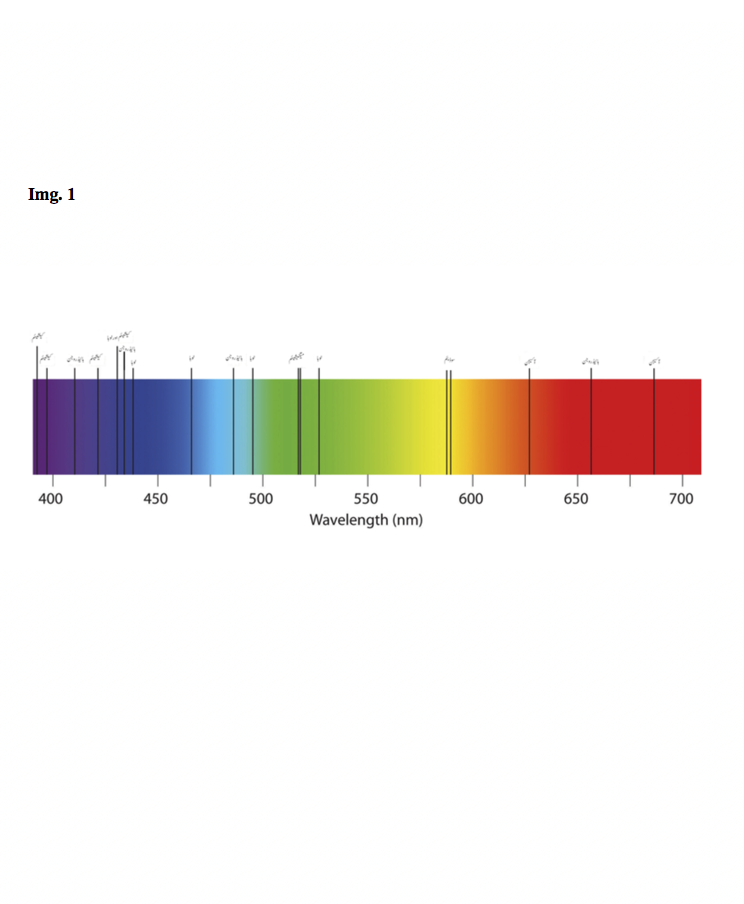

When we look at a spectroscopy image showing a star’s range of wavelengths, certain wavelengths of color will be missing. It might look something like Img. 1.

This is called an absorption spectrum, and the black lines indicate the individual wavelengths which are missing. These wavelengths are missing because of layers of cool, low-density gases, composed of specific elements, such as hydrogen or mercury, surrounding the star. These gases absorb the photons at these specific wavelengths. This photon absorption occurs so that electrons inside these atoms can jump up energy levels and become excited.

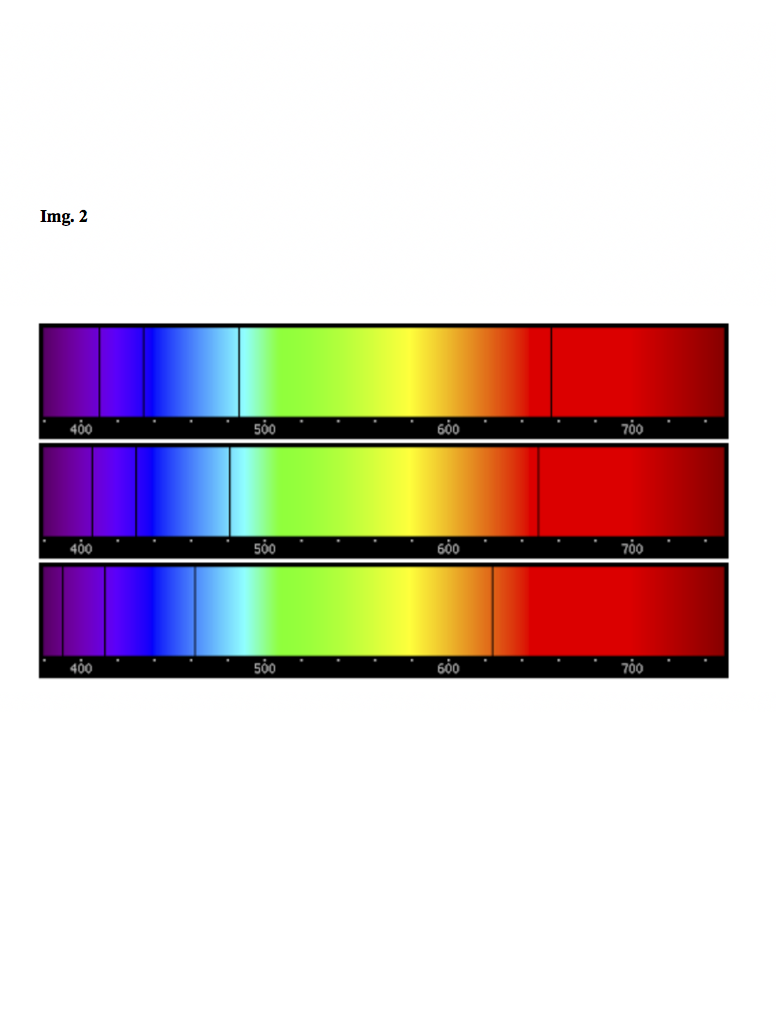

To measure the Doppler effect on a rapidly orbiting star, the black lines of missing wavelengths are shifted back and forth on the absorption spectrum. If they’re shifting towards the blue end of the spectrum, it’s a blueshift; if they’re shifting towards the red end of the spectrum, it’s a redshift. The percentage shift of nanometers that the absorption lines have been shifted is directly proportional to the star’s velocity as fraction of the speed of light. Since we know the value of the speed of light, this allows us to directly calculate the speed of the star that is showing the Doppler shift. See Img. 2.

The Doppler effect might be changing the colors of our world as we use poetry, and stories, and language, as a magnifying or panoramic glass, but in a way, it allows us to grasp the heart of what we value, and to see ourselves reflected in the visions we have chosen. Sometimes, I’ll think back to a younger version of myself crouched over stacks of books in a library at nighttime, conjuring characters as her friends. Every memory, every prediction of a future, is a narrative we so studiously weave to keep our lives linear and focused. We work towards fulfilling those prophecies.

During my gap year, as I step into a poem about family, I see a younger version of myself in the sky, simultaneously moving towards me with her hope and away from me with my growth through the years. The spacetime between the words stretches into the shape of my mother’s mouth and the boom of my father’s laugh crackling over the phone.

Sitting in parks and by lakes, it was first difficult not to feel alone, knowing that all my peers were off to college and that I would be left in California for the next nine months. Solitude was a tactile suit that hung around me like a cage. I questioned what I wanted to do in college and what I wanted to do with my life. Flipping open books under the afternoon light and spending hours reading the worlds moving towards me and away from me that hung unspoken after linebreaks and between paragraphs, I found a way of giving solace to my past and future selves. Whether it’s redshifting or blueshifting, words live as a parallel universe to my reality.

p. 4/4