The Impossible Lesson of Grief

“This framing of grief as something at your service…suggests that grief is not limbic, essential; rather it’s grown vestigial – an appendix best removed before it becomes a problem.”

by Woody Woodger

Pre-Op Thot is a biweekly column by Woody Woodger. “As a transgender anarcho-commie poetry slut, I’m here to derail the economy with my ethically sourced avocado toast and ruin every Thanksgiving with my colonialism PowerPoints. This column will have that same vibe, but I’ll jam poetry and Camus somewhere in there, and you can’t stop me. Through this column, I intend to do bite-sized deep dives into underrepresented aspects of the contemporary Zeitgeist, grounding my discussion with theory, research, and poetry that I think relative to each topic. But don’t worry, it won't all be fun. My teachers, Youtube commenters, and therapist all say my writing is a “huge bummer.” So if you're looking for a column that says “Last-Week-Tonight-but-make-it-discount-Contrapoints,” I’m your gal. So good luck out there, Gorge! God’s dead, smash the patriarchy, and remember sunscreen. Love you!”

My grandmother, Kristin Woodger, passed away in the winter of 2019. This is my reflection on the impossible lesson of grief as I learned it.

Part I | The Impossible Lesson of Grief.

This grandma stuff is so much, Mom says.

She texts me this while I’m home tending to the cat, waiting for the school to call me for some substitute work. Mom and Dad are in Plymouth, Massachusetts, saving me from having to cull Grandma’s house.

This is the third time in three years we have had to get a house ready for escrow – a document kept by a third party and taking effect when a specified condition has been fulfilled. Luckily, we’re running out of family members.

How do whole lives fit into trash bags? How do humans do it? The abacus of our lives flung back and forth until worn, our caskets lowered into a cell in an actuary’s spread sheet.

I think grief is biting a burger and finding a raccoon paw. It’s when the eyes in portraits refuse to follow you.

Everybody is wrong about grief. Let me tell you why. Grief is easy. It’s limbic, glandular. Unfortunately, people can’t seem to help themselves from complicating.

“They jumped from the burning floors—

one, two, a few more,

higher, lower.

The photograph halted them in life,

and now keeps them

above the earth toward the earth.”

– Wisława Szymborska, “Photograph from September 11”

Everybody is wrong about grief, and I’m right, and let me tell you why. Grief is easy. It’s limbic, glandular. Unfortunately, people can’t seem to help themselves from complicating.

Maybe this essay should be another of my shrill, tranny harangues against capitalism and its demand to commodify all human interaction – a more post-worthy, shareable essay. Or maybe it’s more lamentation toward the sexist, patriarchal revulsion at any intense emotional – and thus “feminine” – expression. Regardless, grief falls prey to the same aggravating question that Instagram therapists love to ask: “how does this serve you?”

This framing of grief as something at your service, a tool used to settle the daily bureaucracy of resilience, of “moving forward,” of returning to normal, suggests that grief is not limbic, essential; rather it’s grown vestigial – an appendix best removed before it becomes a problem.

“They jumped from the burning floors—

one, two, a few more,

higher, lower.

The photograph halted them in life,

and now keeps them

above the earth toward the earth.”

– Wisława Szymborska, “Photograph from September 11,” Lines 1-6

Mom says every piece of furniture weeps as we prep the house to be sold. Her clawfoot, antique couch wipes its nose on the bedsheet cover leftover from the Shelties.

They really need to buck up, Mom texts.

Me? Let me press my consciousness into prosciutto. Salted raw. Grandma’s favorite couch was so ancient, the disposal instructions on the tag were in Sanskrit. Grandma’s shelties ravaged that thing, the filigree upholstery diligently excavated by their ungroomed claws. Years ago she threw a bed sheet over that ancient, gorgeous thing. A ghost before it’s time. I look at it now, a heap of legs and hand carved maple. Now I’ll bundle it into the very same sheet, throw the screws in, and write a prayer on the Goodwill donation ticket.

“Each one is still complete,

with a particular face

and blood well hidden.

There’s enough time

for hair to come loose,

for keys and coins to fall from pockets.”

– Wisława Szymborska, “Photograph from September 11,” Lines 7-13

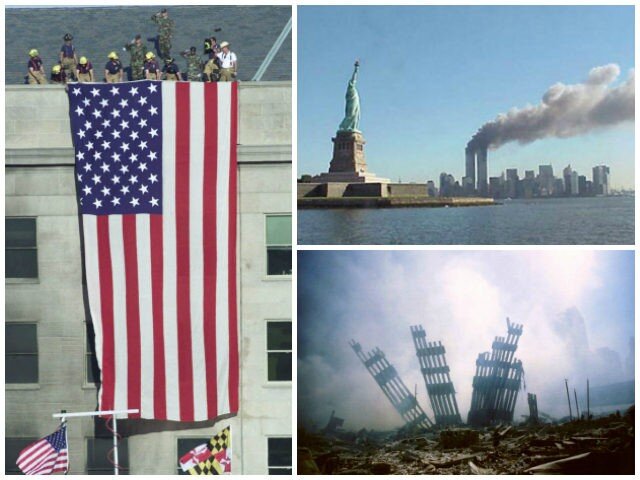

Szymborska’s poem responding to a photograph of 911 victims falling from the Twin Towers illustrates a refutation of grief as something to overcome. The poem goes to great pains, indeed dedicates its bulk to describing how perpetual the horror is.

“Each is still complete, / with a particular face / and blood well hidden,” she writes (7-9). The poem forces the reader to confront the tragic image in perpetuity. As Mark Doty analyzes in his article Can Poetry Console a Grieving Public, “Syzmborska first echoes a familiar 20th-century ethos: she will serve as a witness...But the poet here goes a further, heartbreaking step: she...will not complete the poem (even though it is, in its way, concluded by a refusal). Here, incompletion is an act of mercy.”

But I disagree that incompletion is mercy, here. Rather, I think this poem illustrates grief for what it is: a pain so essential to the body we cannot help but squirrel away bits of our sorrow into the world around us.

Dad can’t do more than assemble piles of papers that recount a life in legalese — Kristin is hereby the proud owner of etc., in two weeks’ time the customer will be expected to pay on behalf of the whole of the family. Why is grief’s first step always escrow?

I envy a grief that is restrained, pragmatic, ship-in-a-bottle impossible. But I also pity it. As a poet, I don’t know a better way to handle my grief than shove every limp morsel into duffle bags and send them off to publishers. Maybe it’s the validation that a poet craves in writing their grief. “Someone might see it,” we tell ourselves, “and then I know it happened, that others care, that I still have some control.”

As the bodies, and faces, and terror, are preserved by chance in the poem’s photograph, so too do we instinctively preserve grief in our bodies, and by extension those belongings – those photographs, files, souvenir ticket stubs, whatever we can bring ourselves to donate – that we feel act as conduit for our grief. These belongings act as a kind of an instinctive record of grieving and can reignite those feelings simply by proximity.

Poetry, really any art, is not as good at encapsulating grief in this way. Any art, poetry included, is always too far removed from grief. Not limbic enough. Grief is not about drafts or synthesis or craft. Poetry does the necessary job of collecting our grief into manageable capsules that take the place of the house she once lived in, the sweater that still smells like that night my brother was born and I stayed with Grandma so a miracle could happen without me.

This phenomenon of art absorbing our traumas is long-documented and has been used as a therapy technique for decades. Writing therapy is a practice whereby clients write and recite to themselves or an audience, a story of a traumatic event so as to work through the pain. Even though the treatment has been successful in alleviating both mental and even physical issues.

And because this is a poet writing, the reason writing therapy is so effective is that by sharing our story, our description of events, we transfer a little bit of our grief into the story. We watch the gestalt of writing and watch the grief hang in the air, remember that it is still there, and here, in this moment, another ounce is left.

The world agrees. According to Philip Meters, “by February, 2002, over 25,000 poems written in response to 9/11 had been published on poems.com alone. Three years later, the number of poems there had more than doubled.” We have a need to flood the world with grief – I believe because we simply see the eternal pain to which we are now betrothed. Through writing, we can understand how to give just a pinch of that eternity a place to live, and settle.

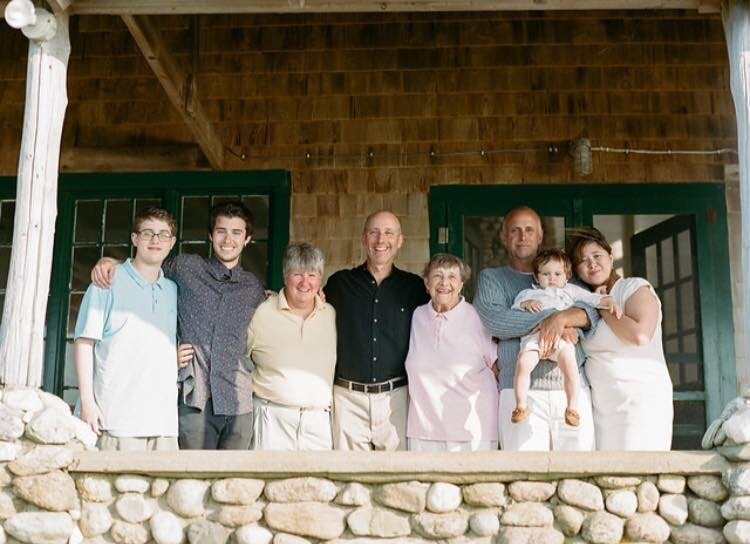

Family portraits featuring my grandmother and 911 memorial images. 911 photos courtesy of Flag in Memorial, 911 Remembrance Collage.

Fine. Inventory—Grandma kicked oxy in her 70’s. Grandma never remarried. Grandma saved her firstborn, twice, with nothing but grit and the runic bedazzlement struck into her hip replacement. Somewhere in the tumbling carousel of hospitals and Dean Koonts novels, she also quit whiskey.

Grandma kept a clutch of souvenirs from Tom Sawyer — my first play. I played Huck. 16 years she kept the playbill, the newspaper clippings, both tickets from both shows. It took me 20 seconds to lose the paperclip.

Grandma waddled, splayed foot, forever tender and uncorrupt, like a penguin dress in coffee stain sweaters. The mail still piles on grandma’s counter. Saint Rose is here sniffing for donations. There are coupons. Bed Bath & Beyond. A red envelope — $25,000 of life insurance, FOR KIDS! Grief knows no address. Best try them all.

Grandma always cried when she chopped onions because Grandma always did penance for the things that died in her arms. Eight decades of dogs, her first born, every orchid wilted on her kitchen table — their hearts to big for the spines. In solidarity, she took their shape. Grandmas planted flowers because motherhood was the way her body spoke.

Grandma would eat glass for the ones she loved, but why so much ceramic soufflé so often?

Grandma loved orchids because they’d stoop with grief from the moment they were born and still, she knew, from them wails beauty. Grandma left us with a house unsellable and a life unreturned.

Grandma was bionic — screws, hips, metal knees, laser attachments, binoculars, magnetized eyelashes, permanent IV ports, wifi enabled, dowsing rods, intravenous USB, dialysis infinitum, the infernal rift between love and suffering, and the epoxy she used to mend the two.

She was a mourn that breaks over every infernal tree like an orange breeze.

Goddamn that she was ever in pain. Goddamn that she held on only to have me lose touch in that impossible way 20-something’s can do. Grandma could hold guilt like it was a purr in her lap.

When they cremate her, there will be almost a full metal skeleton left over. We called her “Terminator.” She called us “achievements.”

Doty says, “To come too quickly to words is, ultimately, a form of arrogance; the easy poem suggests that loss is graspable, that the poet has ready command of speech in the face of anything.” But why not a little arrogance? Why not accept grief in the eternal instant it comes and wail into its agonizing freshness? We should engage with pain like the impossible lesson it is.

No obsession. No Woodger way of hamster wheeling into oblivion. She’d wish me peace. Try to give me all of hers.

I want to be my dad right now. Play engineer. I want to put her back together, reforge her under poetry’s clumsy torch. But she’ll remain there, in ash, with her medical devices and former deeds and yellowed recipes. All these litanies for us to sort through. Piles of things to keep or donate, sell or buy out.

Doty also says it’s no loss that Syzmborska’s poem will not be featured in the New Word Trade Center. He makes a good point. He says, “ I’m all for poetry’s being visible and public…but I fear that public grief is so easily manipulated, and so readily turns to cant…”. And that’s true. And if that manipulation is done with malice, or jingoism, or any other manor of self serving distortion, then I would agree with Doty.

Personally, I also don’t care if her poem is present at the memorial, but not for the same reason. The whole memorial is a monument to manipulating our grief, turning into a tourable event, a “simulacrum of emotion”, as Doty laments. It exists to hold our collective grief and hold it there. So we may move around it, get to it later if we can. What’s one more poem on the walls?

At an unorganized memorial service for 911, Doty recalls the group of people bursting into different songs — “Amazing Grace”, Give Peace a Chance”, “America the Beautiful” — and no group lined up, no group quite found solace or stability or harmony. A grief this messy is exactly how grief should unfold, as a psalm sung incorrectly and confidently.

At the same time, Grandma wouldn’t want me to torture myself, Frankenstein her out of petunias and misremembered Two and a Half Men plot lines. No obsession. No Woodger way of hamster wheeling into oblivion. She’d wish me peace. Try to give me all of hers.

But Grandma, finally, keep something for yourself. Keep your peace. No strings attached, no interest. An eternity at a loss. The angel's share.

Photo of my grandmother (2018)

People talk about survivors’ grief as if it were an anguish that the dead no long have the privilege to life, but really, it’s the shame that you couldn’t follow them. Those shepherdless souls you once had the blundering ignorance to think your love could preserve, now tossed flittering out of your feeble influence.

Every soul like a black speck against the world Trade Center, every loved one evaporating on a hospital bed — our grief is that we did not dive after them into the abyss so they may take you with them.

Grief is a toy left behind never to give their love again. But, reader, hold your grief, your love, so that one day you may have the excruciating honor to love and grieve again.

Woody Woodger lives in Lenox, Massachusetts. Her first chapbook, “postcards from glasshouse drive” (Finishing Line Press) has been nominated for the 2018 Massachusetts Book Awards and her work has appeared, or is forthcoming, from DIAGRAM, Drunk Monkeys, RFD, Exposition Review, peculiar, Prairie Margins, Rock and Sling, and Mass Poetry Festival, among others. Her poetry has been nominated for Best of the Net. In addition, she has a regular column with COUNTERCLOCK Literary Magazine.